Text & Photos: Doug Hyland

orty-five years ago, before fire roads had their own hashtags, the act of off-roading was more of a ramble and less of a digitally enforced itinerary. People were more self-reliant because they had to be. The Scout truck, though in the twilight of its production, was widely regarded as a symbol of freedom and resilience; built to tackle any terrain that our land could offer.

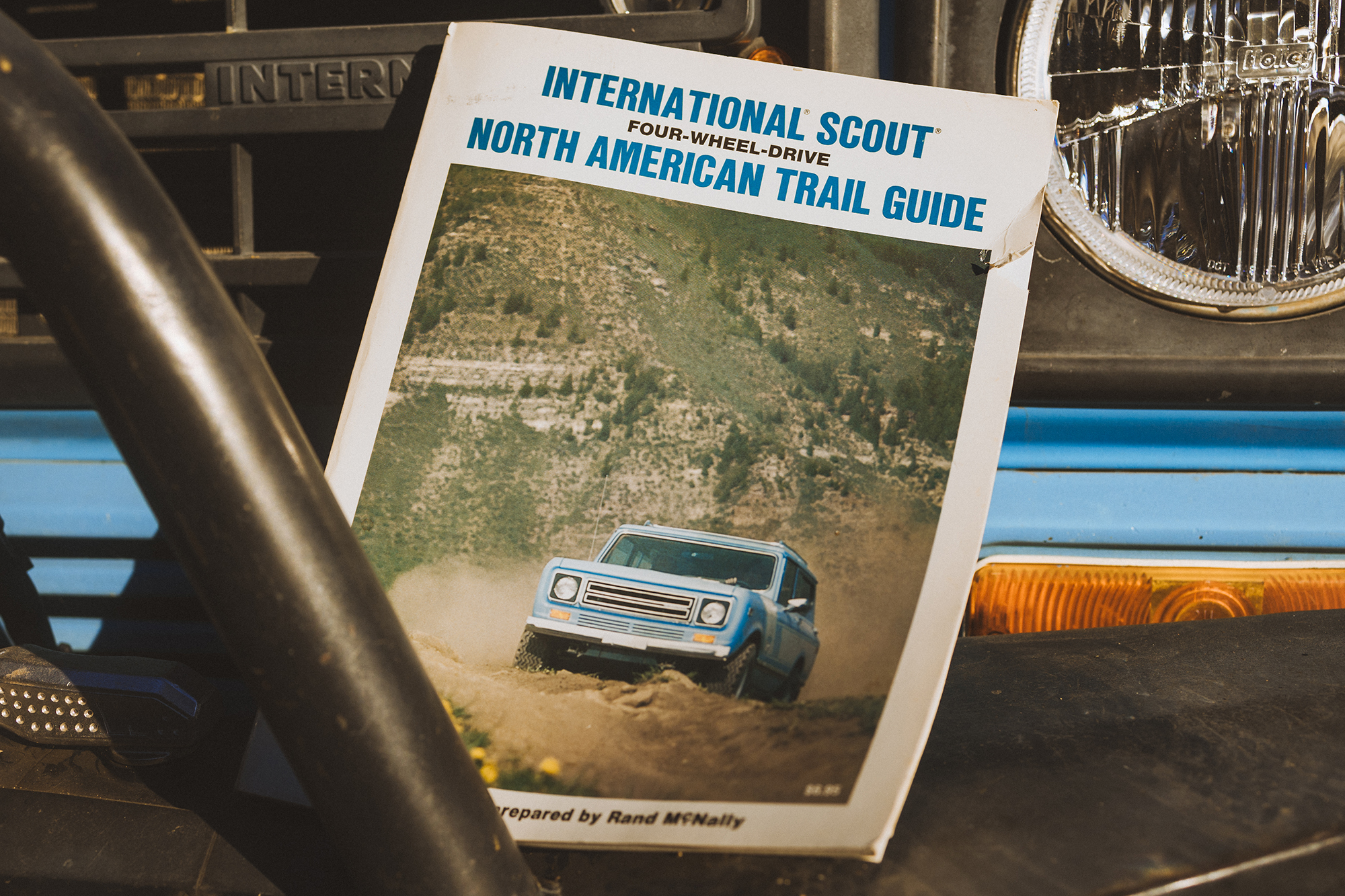

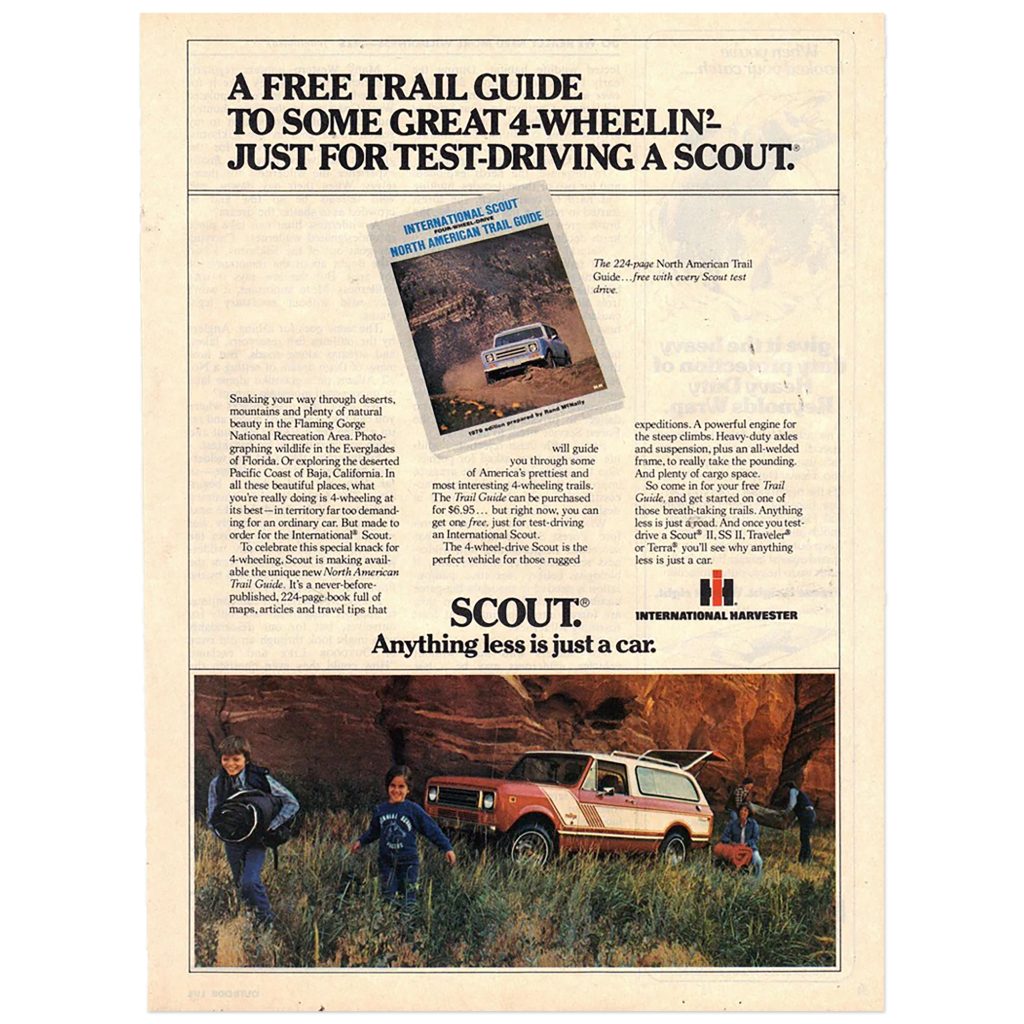

For those who used the vehicle as it was meant to be, the International Scout North American Trail Guide proved to be a welcome companion on the road less traveled.

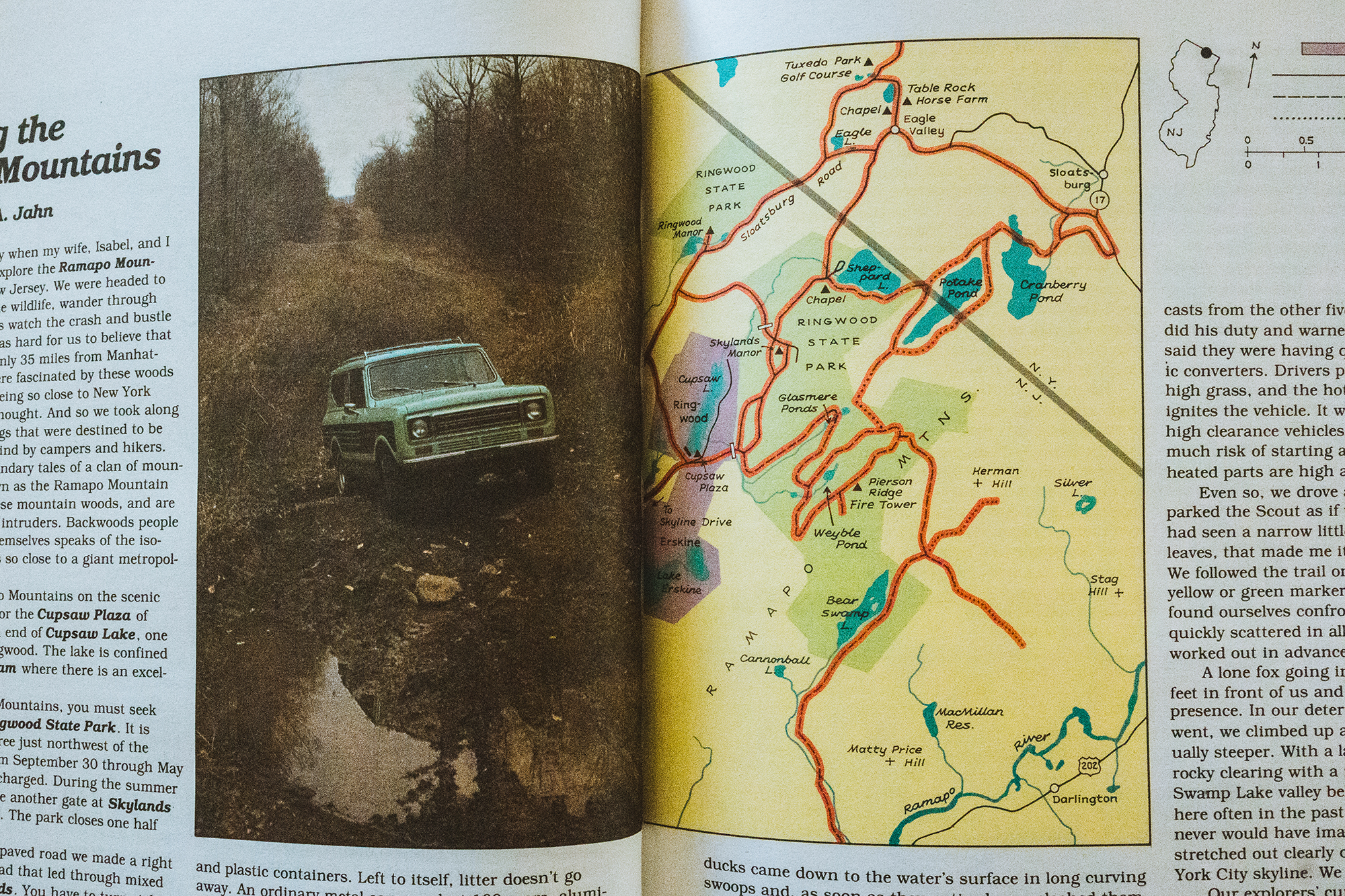

Conceived by International Scout in partnership with Rand McNally in 1979 as a test-drive promotion, the Trail Guide is a repository of knowledge, passed down from the era’s most esteemed outdoor writers. Each trail description is a story unto itself — enlivened by thoughtful prose, hand-drawn maps, grainy photographs, and the whimsical line art that was popular at the time. There are regional wilderness survival tips, off-road driving instructions, and a chapter on the importance of outdoor stewardship, entitled “Take a Stand. Save the Land.”

There are regional wilderness survival tips, off-road driving instructions, and a chapter on the importance of outdoor stewardship, entitled “Take a Stand. Save the Land.”

An opening passage describes how the book came to be: “Each author got behind the wheel of a Scout truck and headed off on an adventure of his own…tracing his own route on a large scale topographic map and sent it to the cartographers at Rand McNally.”

The sum of all of this is an expertly-guided tour across North America, by dirt. It is as much a tool as it is a source of inspiration. Take the chapter on “orienteering”, for example, which suggests that one “take compass readings whenever he comes to a fork in the vehicle trail or road or an intersection” — and then fills several pages thoroughly explaining how to find your bearings in unfamiliar territory. With such guidance, most could master the lost art of pre-GPS navigation. But the immediate takeaway is admiration; both for the contributing writers and for drivers before us. And maybe a little jealousy, too.

They were simply tougher, more patient, and more resourceful in many ways — perhaps even more adventurous. And if we are compelled to drive into the wilderness because of some primal connection to early explorers, then maybe part of the allure of books like this is that they enable a connection to these pioneers of a more attainable, not so distant past. That, and the fact that they also make for an excellent conversation piece when left out on your coffee table.

But beyond the literary and heirloom appeal of this book lies the true value: it is a portal to real, tangible adventure. Because if you thumb through the old maps, you’ll notice something peculiar: most of the surviving trails have faded from the collective memory of the off-road community. Locals and old folks will know about them, sure, but you won’t find them on social media — which means you won’t know what to expect. You also won’t bump into many people, if any, while driving them.

So the reward for your participation is the same today as it was decades ago: A secret campsite, a pristine swimming hole, a cliff dwelling with intact pottery, and little cobs of corn still sitting on the grinding stone. It is your country, frozen in time. And you are Daniel Boone, with light bars and locking differentials, facing an untamed, and un-geotagged, frontier.